The following is a guest blogpost by Ross Mounce, currently a PhD writing on “The Importance of Fossils in Phylogeny” at the University of Bath, in UK. As his approach includes application of informatics techniques to palaeontological data, Ross’s research interests are also oriented towards Openness in Data, Access and Science. Ross attended the Open Knowledge Conference in Berlin, 2011, where he gave a talk on Open Palaeontology.

Ross Mounce:

“A few weeks ago, I gave a talk at the Open Knowledge Conference 2011, on

‘Open Palaeontology’ – based upon 18 months experience as a lowly PhD student trying, and mostly failing to get usable digital data from palaeontological research papers. As you might well have inferred already from that last sentence; it’s been an interesting

ride.

The main point of my talk was the sheer stupidity/naivety of the way in which data is supplied (or in some cases, not at all!) with or within research papers. Effective science operates through the accumulation of knowledge and data, all advances are incremental and

build upon the work of others – the Panton Principles probably sum it up far better than I could. Any such barriers to the accumulation of knowledge/data therefore impede the progress of science.

Whilst there are numerous barriers to academic research (access to research papers being perhaps the most well-known and well-publicised), the issue that most aggravates me, is not the access to these papers, but the actual papers themselves – especially in the digital context of the 21st century. They are only barely adequate (at best) for communicating research data and this is a major problem for the future legacy of our published work… and my research project.

My PhD thesis title is quite broad: ‘The Importance of Fossils in Phylogeny’. Given this title and (wide) scope, I need to look at a lot of papers, in a lot of

different journals, and extract data from these articles to re-analyse; to assess the importance of fossils in phylogeny; to place them on a meta-scale. There are long established data formats for the particular type of data I wish to extract. So well established and easy to

understand there’s even a Wikipedia page here describing the

most commonly used data format (nexus). There exist multiple databases

set aside specifically to host this type of data e.g. TreeBASE and MorphoBank. Yet despite all this

standardisation and provisioning for paleomorphological phylogenetic data – far less than 1% of all data published on, is actually readily-available in a standardised, digital, usable format.

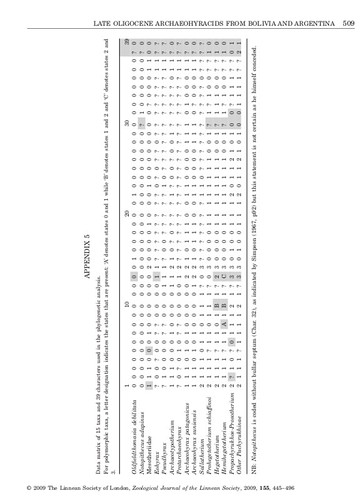

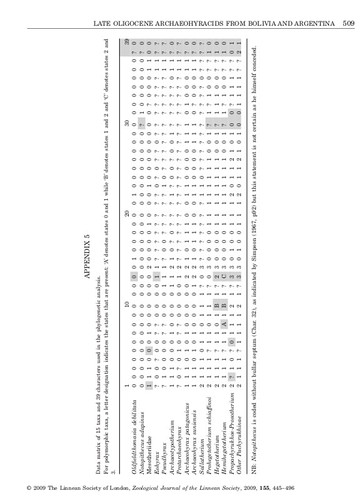

In most cases the data is there; you just have to dig very very hard to release it from the pdf file it’s usually buried in (and then spend unnecessary and copious amounts of time, manually reformatting and validating it). See the picture below for a typical example (and yes, it is sadly printed sideways, this is a common and silly practice that publishers use to inappropriately squeeze data matrices into papers):

I hope you’ll agree with me that this is clearly absurd and hugely inefficient. As I explain in my presentation (also available below this post) the data, as originally analysed/used, comes in a much richer, more usable, digital, standardised format. Yet when published it gets stripped of all useful metadata and converted into a flat, inextricable and significantly obfuscated table. Why? It’s my belief that this practice is a lazy unwanted vestigial hangover from the days of paper-based (only) publishing, in which this might have been the only way in which to convey the data with the paper. But in 2011, I can confidently say that the vast majority of researchers read and use the digital versions of research papers – so why not make full and proper use of the digital format to aid scientific communication?

I argue, not to axe paper copies. But to make sure that digital versions are more than just plain pdf versions of the paper copy, as they can and should be.

With this goal in mind, I set about writing an Open Letter to the rest of my research community to explain why we need to richly-digitise our published research data ASAP. Naturally, I wouldn’t get very far just by myself, so I enlisted the support of a variety of academic friends via Facebook, and (inspired by OKFN pads I’d seen) we concocted a draft letter together using an Etherpad. The result

of this was a fairly basic Drupal-based website that we launched

http://supportpalaeodataarchiving.co.uk/ and disseminated via mailing lists, Twitter, Academia.edu as far and wide as we possibly could, *hoping* just hoping, that our fellow academics would read, take note and support our cause.

Surprisingly, it worked to an extent and a lot of big names in Palaeontology signed our Open Letter in support of our cause; then things got even better when a Nature journalist (Ewen Callaway) got interested in our campaign and wrote an article for Nature News about it, which can be found here.

A huge thanks must go to everyone who helped out with the campaign, it has generated truly International support, as can be demonstrated on the map below:

(View Open Letter Signatures in a

larger map)

It’s far too soon to know the true impact of the campaign. Journal editorial boards can be very slow to change their editorial policies, especially if it requires a modicum of extra effort on the part of the publisher. Additionally, once the editorial policy does change at a journal, it can only apply to articles submitted from henceforth and thus articles already in the submission pipeline don’t get affected by any new guidelines. It’s not uncommon for delays of a year between submission and publishing in palaeontology, so for this and other reasons, I’m not expecting to see visible change until 2012, but I think we might have helped get the ball rolling, if nothing else…

The Paleontological Society

journals (Paleobiology

and Journal of

Paleontology) have recently adopted mandatory data submission to

the Dryad repository, and the Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology has also improved their editorial

policy with respect to certain types of data, but these are just a few of many journals that publish palaeontological articles. I’m very much hoping that other journals will follow suit in the next few months and years by taking steps to improve the way in which research data is communicated, for the good of everyone; authors, publishers, funders and readers.

Below you can find the Prezi I used to convey some of that (and more) at OKCon 2011. Huge thanks to the conference organisers for inviting me to give this talk. It was the most professionally run conference I’ve ever been to, by far. If the conference is on next year – I’ll be there for sure!”

Ross Mounce

The invited talk, given on Friday 1st July 2011 at the Open Knowledge Conference (Berlin) by Ross Mounce: Open Palaeontology on Prezi