Open Science at Tech4Dev 2014

The session ‘The Openness Paradigm: How Synergies Between Open Access, Open Data, Open Science, Open Source Hardware, Open Drug Discovery Approaches Support Development?’ covered a range of topics reflecting the breadth of practices that constitute open science but the two key areas of interest were open hardware for science and open data.

First speaker up was Professor Irfan Prijambada from Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, who described the necessity of access to lab equipment for his microbiology research focused on agricultural practices and fermentation. Fermentation is important for alcoholic drinks but also the fermentation of cassava and rice to produce traditional Indonesian foods such as tapei. Further aspects of research in the Laboratory of Agricultural Microbiology centre around soil and water microbiology, including biodegradation and bioremediation in volcanic soils. As any microbiologist knows, the ability to observe small lifeforms and a sterile environment in which to culture and work with them are the two most essential research requirements in the lab. Prof Prijambada described the resultant difficulties of performing research effectively when dealing with obsolete and inadequate research equipment, relying on out of date microscopes with no digital image collection and plating microorganisms on agar in open spaces next to a bunsen burner with no access to a clean hood or laminar flow hood, both standard pieces of equipment for maintaining a near-sterile environment and ensuring samples are not contaminated. To add to these difficulties, applying for funding for equipment procurement at the university can mean a 12 month wait for processing and delivery even if the application is approved. There was a clear need for cheap, rapid and local supply of essential kit.

Step in Hackteria.org. In 2009 after a workshop in Yogyakarta run by Marc Dusseiller, an active maker and advocate of DIY biology and open source hardware, Prof Prijambada and his lab set about taking a DIY approach to lab hardware by creating their own clean hood and laminar flow hood, initially using a glassfibre filter but now employing a series of HEPA filters. The equipment was constructed in only 2 months for less than 10% of the cost of a commercial equivalent (1.2m IDR vs 15m IDR). Microscopes were constructed from webcams in less that one month costing 750k IDR instead of 7m IDR and were entirely adequate for research needs. Not only adequate, but aquisition of digital images allowed an automated colony counter to be developed. The importance and utility of these microscopes was explained by their developer Nur Akbar Arofatullah, a researcher at Gadjah Mada University, who founded the Lifepatch initiative and along with other hardware projects, has improved the DIY microscopes to the stage where a company is now offering a commercial version of the latest MiCAM v3.2 for those who don’t find DIY appealing. However, hands-on construction remains a key part of the educational aims of open hardware and Lifepatch are using the microscopes and their construction for a range of workshops pitched at different educational levels. Kindergarten students compare the width of their hair in Cyber Hair Wars, elementary students learn about plant and muscle cells, high school students construct their own microscopes while their teachers are taught how to run workshops themselves. University students are enthused with the DIY spirit and encouraged to apply these principles in their own education and research.

One area where Gadjah Mada University excels is community relations. Setting an example for all publicly funded research establishments, staff and students are expected and obliged to work with the community to achieve promotion within the university and there exists a dedicated Office of Research and Community Development. Within this ethos, DIY microscopes have been used to bridge knowledge between the university and community through workshops on sanitation and hygiene which make use of the microscopes and microbiology techniques to analyse water, take handswabs and analyse data on E. coli contamination. Lifepatch have run the Jogja River Project for several years, taking an integrative approach to water quality and river monitoring including participatory mapping and data collection on vegetation and animals all the way through to active clean up operations. Innovation in DIY hardware is rapid at Lifepatch and Gadjah Mada, with other projects including a vortex, rotator for incubating bacterial samples and a pipette stand. As per the example of MiCAM, the DIY approach is still compatible with commercialisation as people can buy pre-built hardware, thus offering the possibility of generating jobs and income but there are many questions around models for these activities which were of interest to the audience but could easily fill an entire session and were not covered in any depth (see reports here and here for an introduction).

In a related talk during a later session at a beautiful UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Lavaux vineyards on the banks of Lake Geneva, Dara Dotz presented on 3D printing open hardware during another session which touched on the creation of jobs and hyper local digital manufacturing capacity in Port au Prince, Haiti. Dara travelled to Haiti for three weeks and ended up staying for a year working for an NGO. She observed problems in water treatment plants and in hospitals which were caused by a lack of supplies and particularly spare parts due to a broken supply chain including long shipping and customs quarantine times, a culture of bribes and poor transport links for distribution. After a friend attended the delivery of 5 babies in one evening and had no option for tying off umbilical chords but using her own gloves, Dara realised that her background interest and contacts in 3D printing could be used to solve some of the issues of obtaining plastic parts and consumables. Having brought a Maker-bot 3D printer into Haiti, Dara trained a group of Haitians with basic education to use the printers and 3D design software and several potential uses were identified, with critical application being umbilical chord clips, splitters for oxygen tubing to allow multiple patients to receive oxygen from the same cyclinder and IV bag hooks to reduce the use of large IV stands which blocked space in already overcrowded wards.

3D Printing Umbilical Cord Clamps for babies in Haiti! from Not Impossible on Vimeo.

There were many considerations and design challenges to be addressed such as ensuring that designs addressed community needs and were designed with, by and for local people. In addition to empowering people to produce there own solutions to address real-time problems, the manufacturing method has the benefit of being on-demand, helping to ensure cleanliness of equipment, provides jobs and is also cheaper than importation of commercial equipment. Umbilical clips can be manufactured for $0.36 compared to $2.69 imported cost, representing a significant saving over time in this resource poor setting. Dara is now applying the same ideas to disaster zone supplies through the NGO fieldready.org and plans extensions to the Haiti project including importing CNC machines to allow manufacture of metal parts, creating a repository of designs for field supplies and increasing the use of recycled plastic waste for non-clinical devices and prototyping.

The Open Source Hardware approach advocated throughout this session is supported by the Open Source Hardware Association (OSHWA), a non-profit aiming to raise awareness of OSHW and to spur innovation by hobbyists, commercial and academic users. Gabriella Levine is President of the OSHWA Board and an artist with an interest in snake biomimicry. She introduced two projects designed for sensing water quality and clearing oil waste – Protei and Sneel, a snake biomimetic robot designed iteratively by Gabriella and documented online.

two sneels together playing from gabriella levine on Vimeo.

PROTEI PRESENTATION VIDEO from toni nottebohm on Vimeo.

These modular sailing and swimming robots allow sensors for oil, plastic waste,temperature, radioactivity and more to be attached and move through the water autonomously or via remote control, taking readings as they go. These concepts have been used in a range of water quality workshops and Gabriella runs hackdays exploring ideas around the design and deployment of water quality monitoring sensors and other hardware, including a water hackathon at Tech4Dev the following day!

With a variety of DIY and OSHW approaches and designs being prototyped and promoted in areas as important as sensors and even medical devices, a major question becomes how to ensure that quality is consistent and devices work accurately and safely. The current systems of quality assurance regulations in various countries are often either complex, expensive, time-consuming and a massive barrier to market entry – or non-existent. Kate Ettinger is working to develop a system for collecting information on quality and accuracy of OSHW projects in an open and transparent way using an open source hardware/software data collection system and an open data approach to making information available. This framework could apply to many projects but Kate used the examples of neonatal incubators and prosthetic limbs, with data being collected to accelerate responsive design and ensure ‘integrity by design’ throughout the development and deployment of open source medical devices.

OpenQRS in 30 Seconds from Kate Ettinger on Vimeo.

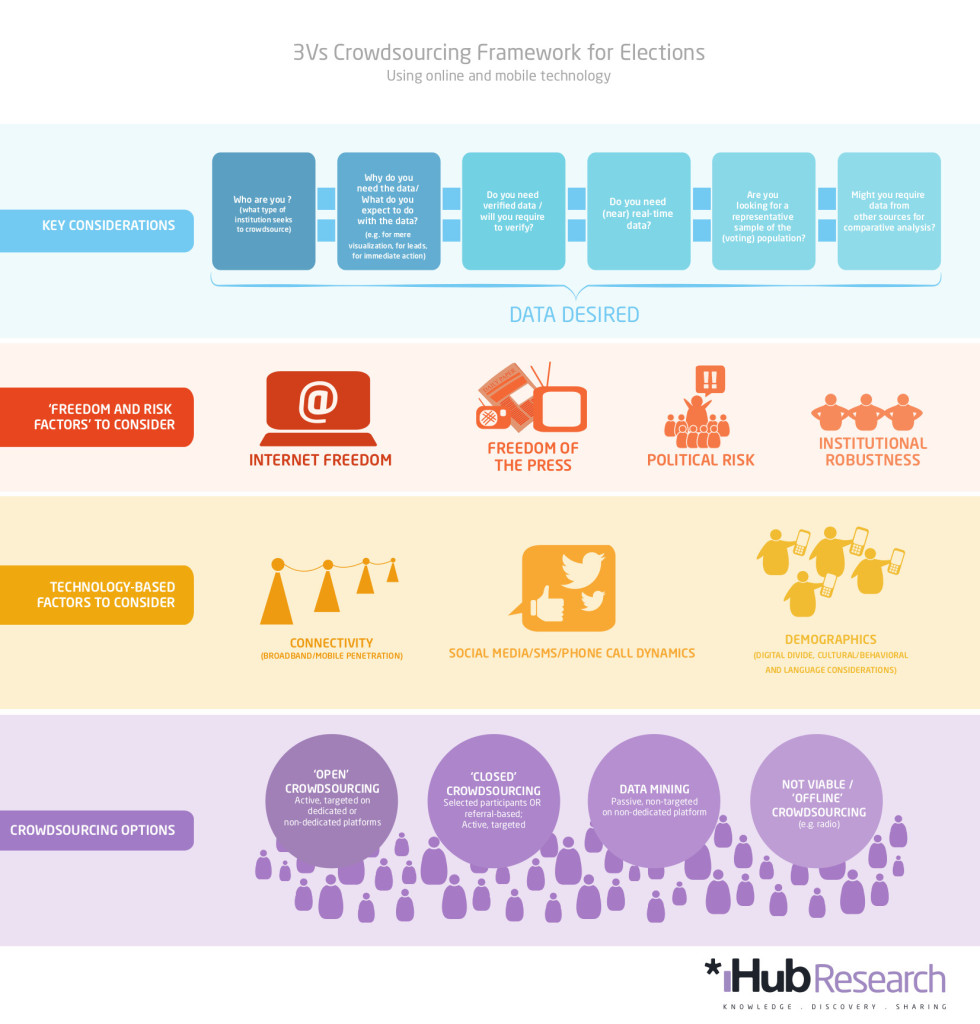

From open data for open hardware to open data as a research tool, Nanjira Sambuli from iHub in Nairobi described the use of crowd sourced data during the Kenyan elections in 2013 and contrasted data collected from Twitter and other social networks via passive crowdsourcing with active sourcing organised by Ushahidi. Conclusions presented were that machine learning algorithms are necessary to make collection of large datasets from high volume social networks viable and that there were surprising patterns and voices gathered through passive listening rather than active calls for information. Nanjira presented a framework developed by iHub for election data crowdsourcing emphasising the three V’s – viability, validity and verification.

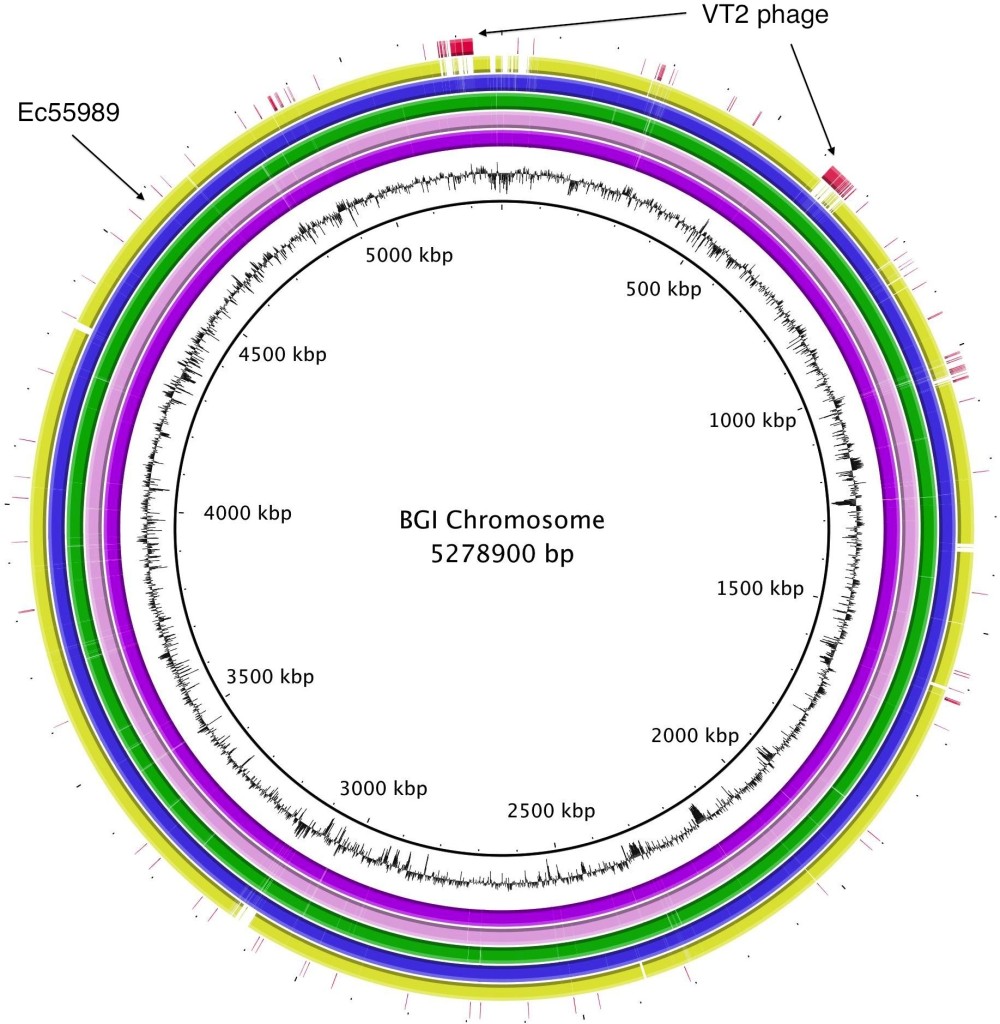

Integrity and curation of scientific data was also highlighted in the final talk by Scott Edmunds of GigaScience , during which he described some excellent case studies of the power of openness. One example was increasing the rapidity of disease research during the E.coli outbreak in Europe in 2011, where BGI rapidly sequenced and released the genome as open data. The image of the chromosome map was later chosen as the front cover of a major report from The Royal Society in the UK on openness in science. Another example looked at the great scope for crowd sourcing the collection and analysis of open datasets. Research on Ash Die Back, an invasive tree disease, demonstrated several flavours of citizen science from publicly contributed geo-tagged photos of infected trees for OpenAshDB to gamification of genome data analysis via the Facebook game Fraxinus. It is also clear that citizens are very keen to support local research that is important for them and wish data to be made public to enrich their scientific and cultural heritage. The Puerto Rican “People’s Parrot” genome project took an endangered and much loved national symbol and sequenced its genome to learn more about its uniqueness and evolutionary history. This effort was funded by fashion shows, art projects, concerts, a branded beer and public donations. Scott focused on these successes but also discussed the challenges in increasing open data release, including ensuring researchers get appropriate credit and are incentivised to make their data available.

A common theme running through the presentations was that openness can be effective at accelerating innovation and enabling research in resource-poor settings. In addition, the scope for education and democratisation of the scientific process through involvement of local communities in scientific research and technological innovation has variously led to employment, empowerment and increased opportunities. The challenge now is to establish under what contexts this remains true and work to advocate and support open approaches where they can offer benefits for scientists and citizens in the global South. I hope members of this working group and the rest of the global open science community will be able to contribute to this mission!

[…] aims of the DIY movement tied in with this conference are succinctly illustrated by Jenny Molloy in this article. The Water Hackathon took place on 6 to 7 June and it is co-produced by Bio-Design for the Real […]